Мозаїчний дамаск

Дамаську сталь виготовляють методом багаторазового ковальського зварювання пластин, що відрізняються одна від одної своїм хімічним складом і, отже, кольором після травлення. «Мозаїку» також виготовляють методом ковальського зварювання різнокольорових сталей – і методом досить давнім. За старих часів при виготовленні високоякісного дамаска іноді зварювали не стопку плоских пластин, а пучок тонких прутків або дротів. В результаті отримували візерунковий метал, що складається не з пластин-шарів, а з прутків-волокон.

Такий великоволокнистий метал і став основою для «мозаїчного» дамаска. Для його отримання знадобилося лише розташувати різнорідні прутки в пакеті не абияк, а в строго заданому порядку - так, щоб після ковальського зварювання на поперечному зрізі утворилася свого роду сталева мозаїчна картинка. Для складання цієї мозаїки могли використовуватися не тільки тяганини та вузькі пластини, але й спеціально виготовлені прутки дуже складного поперечного перерізу. Залежно від конкретного порядку розташування цих різнорідних елементів візерунок поперечного зрізу звареного візерункового блоку міг бути як завгодно складним.

Найбільш простий у виготовленні візерунок утворюється при наборі блоку з прутків та пластин прямокутного поперечного перерізу. Наочними прикладами є візерунки типу «шахова дошка» і «хрестовий». Того ж рівня складності сітчаста мозаїка, одержувана зварюванням брикету безлічі сталевих прутків квадратного поперечного перерізу з прокладеними між ними тонкими пластинками контрастного металу.

Більш трудомістким є виготовлення блоку з орнаментом у вигляді букв, багатопроменевих зірок та їм подібних елементів. Наприклад, східні рушничні майстри любили візерунок у вигляді зрізу лимона або рулету, а їхні європейські колеги навіть примудрялися виявляти на стовбурах зі «шрифтового» дамаска написи, що непогано читаються. Вихідні блоки з такими візерунками можна було зварити в моноліт, лише використовуючи спеціальні оправлення та підкладки, інакше пучок різнорідних волокон розповзався під час проковування.

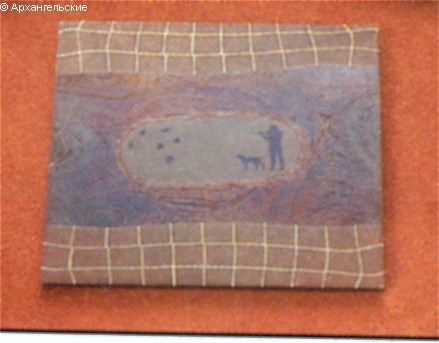

Ще більш складною технікою є зварювання блоків мозаїки з реалістичними фігурами людей, тварин тощо. Для складання вихідного пакета застосовуються бруски сталі, в яких електроерозійним способом зроблено наскрізні фігурні вирізи. У ці бруски, що служать матрицями, вставлені точно відповідні вирізам фігурки-вкладиші з іншого, контрастного металу.

За іншим варіантом, як матриця-наповнювач використовується дрібний металевий порошок заліза, сталі або нікелю, засипаний в тонкостінний контейнер. У цей контейнер поміщають прутки складного перерізу із зачищеною поверхнею або зігнуті зі стрічок та пластин фігури будь-якої конфігурації. Наприклад, у вигляді бутонів квітів, фігур людей чи тварин. Елементи-вкладиші можуть також виготовлятися методом електроерозійного різання тонким дротом. Засипавши ці композиції порошком і загерметизувавши контейнер, його нагрівають до температури зварювання і акуратно проковують з 4-х сторін.

Проковують дійсно акуратно та ретельно. Іноді навіть неймовірно акуратно... Першопрохідник сучасних способів виготовлення мозаїчного дамаска Стівен Шварцер 1993 року відкував мозаїчний пакет для свого ножа «Мрія мисливця» - і кував його шість місяців із перервами. За цей час він «лише» розкував брусок діаметром 130 мм з вставленою в нього багатоелементною фігуркою мисливця так, що його «зріст» зменшився з 40 мм до 12 і його стало можливим вварити в клинок ножа. Нюанс у тому, що у фігури мисливця можна розглянути навіть підбори на чоботях і, що найпримітніше, після всіх деформацій при зварюванні та проковуванні стовбур біля рушниці залишився прямим. Якби навіть такий складний блок кувався так, щоб у результаті вийшла не більш ніж впізнавана фігура, то кування всього клинка (без урахування підготовки вихідного пакета) зайняло б пару днів, а то й менше. У цьому випадку робота майстра у сенсі акуратності може бути свого роду шлагбаумом у техніці мозаїчного дамаска – все, глухий кут, далі цим шляхом йти нікуди.

Використання сучасних порошкових технологій при виготовленні мозаїчного дамаску робить цю роботу для більш-менш досвідченого коваля дещо схожою на дитячу гру. Можна лише змагатися у химерності задуманого візерунка та ступеня наближення старанності та трудомісткості до вершин технології «кам'яна дупа». Виняток – рідкісні, небагато майстрів, які застосовують оригінальні методи, для розробки та використання яких потрібна не тільки старанність ремісника, а й неабияка напруга розуму майстра. Ніхто не скасовував і поняття художнього смаку, без якого створення клинка з гармонійним візерунком важко і навіть малоймовірне.

Проте, про клинки… Після акуратного зварювання та проковування вихідного складного візерункового блоку справа залишалася «за малим» – відкувати з цього дамаска клинок. Різко неоднорідна, великогалущена мозаїка сама по собі не має хороших ріжучих властивостей, тому для надання ножу пристойної утилітарності його тим чи іншим способом забезпечують твердим лезом з багатошарового дамаска, а для міцності іноді наварюють і в'язкий обух. Втім, треба обов'язково відзначити, що іноземні майстри дуже часто відверто і з розмаху плюють на пристойності, відковуючи такі мечі, якими не те що олівець, а навіть сірник краще не заточувати. Але, загалом, на Заході особливої утилітарності від мозаїчних клинків і не потрібно - був би візерунок красивішим і складнішим, а ім'я майстра відоміше ...

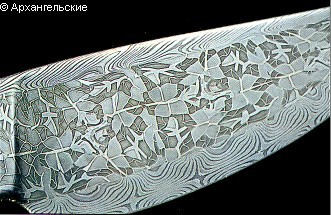

Для того, щоб «показати товар обличчям», цей хитромудрий візерунок мозаїки потрібно якимось чином проявити на бічних поверхнях клинка. Майстри використовують три основні методи прояву візерунка мозаїчного дамаска, отримуючи в результаті кручену, розгорнуту і торцеву мозаїку.

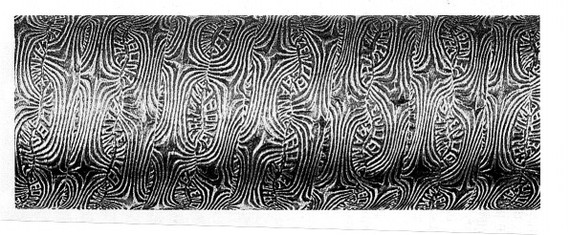

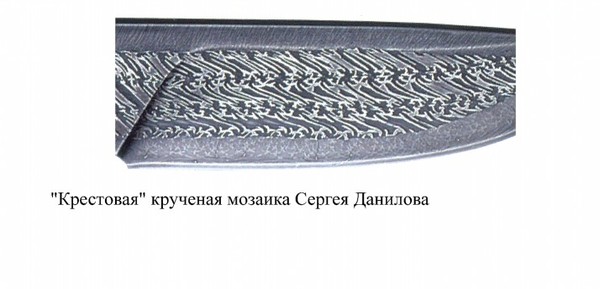

«Кручена» мозаїка фактично є різновидом т.зв. турецького дамаска. «Крученою» мозаїкою дамаск назвали тому, що його одержують шляхом скручування тонких складених візерункових прутків, які для зварювання складаються у вузьку високу стопку. Як правило, в мечі мозаїчна основа складається з 3-5 зварених воєдино туго закручених прутків. Для надання клинку більшої стійкості при згинанні ці прутки часто закручують у різні боки – за годинниковою стрілкою та проти. Після шліфування на поверхні клинка проявляються повторювані з кроком закрутки фігури (одна фігура на оборот), закладені в первинний блок. Чим глибше зішліфовуються площини клинка, тим повніше і чіткіше розкривається візерунок.

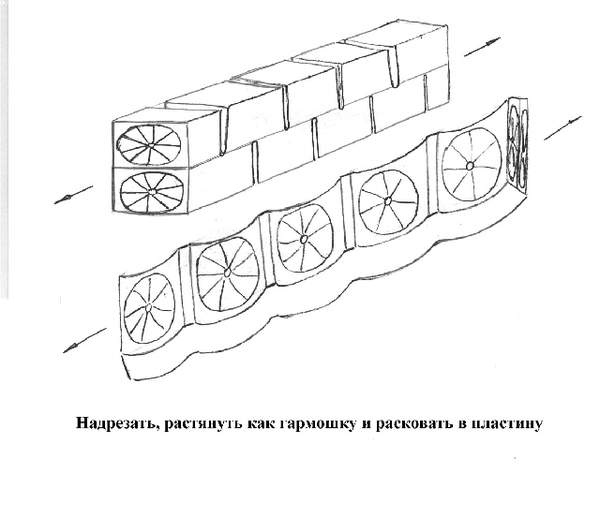

«Розгорнута» мозаїка ґрунтується на цьому ж принципі «розтину». На заготівлі клинка з двох сторін, зі зміщенням на півкроку, роблять кілька глибоких (приблизно на половину товщини) V-подібних надрізів, а потім розтягують її в гарячому стані як гармошку, наче розгортаючи топографічну карту або паперовий віяло з орнаментом. Надрізи роблять кутовими, щоб полегшити розгортання заготовки та щоб вона не порвалася вздовж волокон. Чіткість і ступінь прояву первинного візерунка залежить від глибини та кроку нарізів, а також від подальшої деформації.

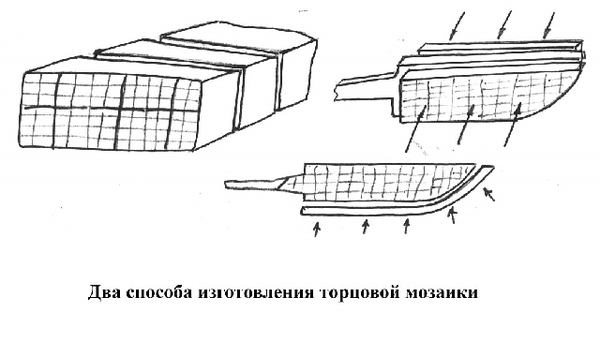

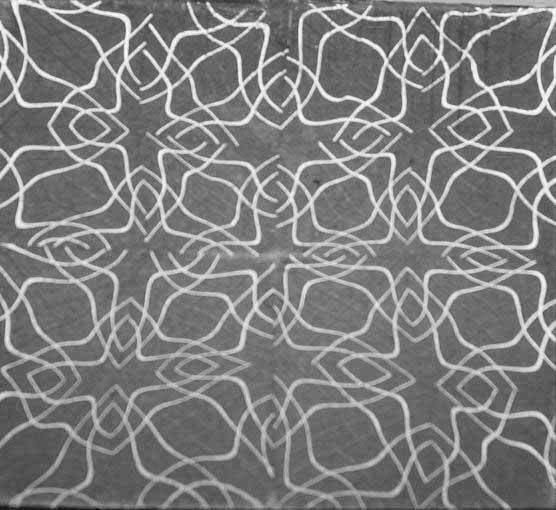

У «торцевій» мозаїці узор спотворюється найменшою мірою. Для виготовлення клинка з торця (звідси і назва) готового візерункового блоку упоперек волокон зрізають візерунчасті пластинки, до яких потім або приварюють лезо та обух, або наварюють їх з двох боків на пластину з лезового металу. Хоча знову ж таки можна повторити, що багато майстрів зараз просто вирізають із пластини торцевої мозаїки заготівлю клинка, не обтяжуючи себе спробами надати хоч якусь утилітарність клинку навіть із вкрай неміцної торцевої мозаїки, в якій ослаблені тонкі зварювальні шви розташовані поперек смуги.

Отже, розробка виробництва мозаїчного дамаска, загалом, зрозуміла. Якщо говорити "не загалом", то можна навести і примітні прийоми роботи майстрів. Так, колись своєю «розгорнутою» мозаїкою з нержавіючих металів мене здивував Девін Томас. Його дамаск складався з безлічі квадратних зволікань нержавіючої сталі 440С, пересипаних між собою порошком нікелю, який, ясна річ, теж не іржавіє. Візерунок такого класичного «розгорнутого» дамаска, сітчастий у своїй основі, дуже схожий на топографічну карту. Примітно, що цей продуктивний американський коваль запасся надзвичайно гарним набором обладнання, оскільки, як він сам говорить у суто американському стилі, обладнання економить час, час - це гроші, а грошей завжди не вистачає. Не знаю, чого не вистачало американському професору на пенсії Хенку Кнікмейеру, коли він вирішив зайнятися «торцевою» мозаїкою, але він домігся того, що його мечі довгий час служили еталоном, свого роду класикою «торцевої» мозаїки. Наскільки я знаю, він одним із перших став регулярно виготовляти клинки з візерунком, складнішим, ніж простий набір квадратиків та платівок. Похвально, що свої мечі він практично в обов'язковому порядку постачав і твердим лезом, і пружним обухом.

За технологічною складністю візерунків його в ті часи перевершив лише вкрай честолюбний і акуратний Стівен Шварцер, який крім «Мрії мисливця» того ж 93-го року зварив клинок з візерунком у вигляді власного розгонистого підпису, який потрібно було розглядати в мікроскоп. Навіть після розковування пакета підпис був дуже чітким і читаним.

Національний герой Франції П'єр Ріверді не став ні з ким змагатися в акуратності. Для виготовлення складних елементів мозаїки він, подібно до Шварцера, купив дорогий верстат електроерозійного різання і навчився самостійно складати для нього програму. А далі майстер пішов своїм шляхом, виготовляючи дамаск, який він сам назвав «поетичним». Наприклад, наприкінці 90-х років він виготовив великий клинок з «крученої» мозаїки, яким «бігло» безліч дрібних фігурок, у яких можна було впізнати єдинорогів. Втім, якщо відволіктися від авторів різного роду «образів» і «ідей», то чисто з технологічної точки зору в «поетичному дамаску», за мірками сьогоднішнього дня, немає нічого особливо хитромудрого.

Однак коваль він не просто вправний, а талановитий. Наприклад, блиснувши технікою ковальського зварювання, він відкував унікальний складаний ніж Пер де Ноель (Дід Мороз по-нашому). Побачивши його фотографію, я за звичкою почав дробити візерунок клинка на складові, щоб зрозуміти, як він зроблений, але досяг далеко не відразу. Легко було зрозуміти, як виготовлені окремі елементи, але як із них зварений сам клинок – це була загадка, яка не вкладалася у звичайну схему мозаїки – кручена, торцева, розгорнута. Для мене ключем послужило те, що кожен четвертий олень у крученій (на перший погляд) мозаїці біжить в інший бік! Зачепившись за цю деталь і згадавши прийоми виготовлення дамаських рушниць, мені вдалося покроково розшифрувати технологію. Якщо сказати коротко і спрощено, то Ріверді намотав візерунчасті прутки самі на себе, як мотузку в бобіні, а потім проварив цей клубок у моноліт і вирізав із його середини заготівлю клинка.

Це називається – свобода. Свобода в тому сенсі, що при досягненні певного рівня майстер вже не пов'язаний технологічними схемами (кручена мозаїка або ще якась), важливий лише задуманий візерунок. Фактично, досвідчений майстер може втілити чи не будь-який мислимий візерунок, наскільки складним він би не був. Обмеження, мабуть, лише у психофізичних особливостях особистості людини, у його схильностях та здібностях до зосередженої акуратності чи натхненної поетики.

Ну, треба сказати дещо й у комерційному (чи, якщо завгодно, мистецтвознавчому) плані, бо сьогодні мозаїчні мечі є преметом колекціонування нарівні з картинами. Я вже якось писав, що за японськими поняттями скарб має володіти трьома неодмінними властивостями – рідкістю, чистотою (у духовному сенсі) та високою вартістю. Щодо духовної чистоти – це дуже навряд чи, від святості ми далекі, але ціна є присутньою, причому іноді дуже чимала. Наприклад, відома фірма «Холанд-і-Холанд» продала одну із робіт П'єра Ріверді за 180 тисяч швейцарських франків – це приблизно 100 тисяч доларів. Мені розповідали, що ніж Пер де Ноель не раз перепродувався і черговий власник здав його через аукціон Крісті. Кажуть, лише комісійні фірми становили 80 тисяч доларів! Сучасний скарб у вигляді шматка візерункового заліза.

© Леонід Архангельський

— середнє 2-300x300.jpg)